this story is from August 29, 2020

‘Birds are amazing builders — their nests show diverse ways of protecting a family’

Richard Prum is the William Robertson Coe Professor of Ornithology at Yale University

Richard Prum is the William Robertson Coe Professor of Ornithology at Yale UniversityRichard Prum is the William Robertson Coe Professor of Ornithology at Yale University. A recipient of the MacArthur Fellowship, and author of the Pulitzer Prize-finalist book ‘The Evolution of Beauty: How Darwin’s Forgotten Theory of Mate Choice Shapes the Animal World and Us’ (2018), Prum is an eminent authority on avian life. Sharing his insights with Times Evoke, Prum discussed the architecture of birds’ nests, their functionality — and their beauty:

Birds have been building nests for over 100 million years. Dinosaurs, the ancestors of birds, also built terrestrial nests over hundreds of millions of years. The diversity we see in birds’ nests today is a result of these thousands of bird species, evolving in different environments, creating diverse ways to house and protect a family. We think of architecture as a consequence of conscious design, purpose and aesthetic expression — there is precisely such architecture in avian nests. These are not haphazard constructions. These are shaped by a history of selection and functionality.

Also, the diversity of materials used by birds to build nests is astonishing — and birds arrive at these independently. As adults, they go out into nature alone and gather materials to construct their nests which have very specific structures. These are extraordinary building capacities which show both flexibility and an innate way of interacting with the environment. Interestingly, all nests perform a physical job — to house and protect a bird’s eggs, most vulnerable to weather and predators. The nest is also often the location of the development of the young.

Therefore, knowing the nest’s centrality, birds have developed habitat-based strategies to meet these needs. Diverse species use sticks, twigs, webs or mud, handled in specific ways to create the nests they require. Like human builders, birds choose materials related to the actual structure they want. Birds’ nests also have persistent styles of construction — these are historically contingent, like human communities which use bricks or shingles. Birds have a similar historical investment in their nests. For instance, a group of land birds, which includes kingfishers, hornbills, toucans and woodpeckers, is about 60 million years old. All of these nest in holes, from ground burrows to holes in trees, where they can safely keep their eggs. None of them has created an alternative way.

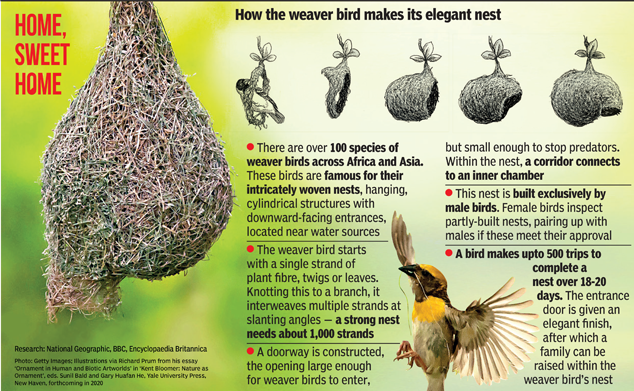

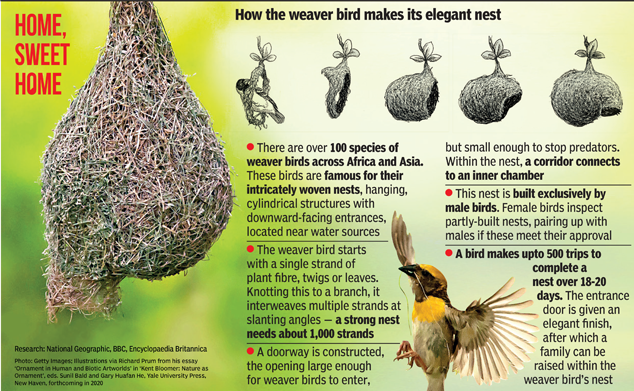

Nests are therefore conservative structures — birds don’t change the designs much, unless they are sure they are improving on the conditions required for breeding and protecting their young. Now, weaver birds are an extraordinary example of a group that makes spectacular nests. These include an egg chamber suspended from a branch, with a doorway. The complexity is amazing — the fibres are interlaced, like weaves. This creates very strong water-repellent structures. The weaver bird starts with a vertical ring, like a hoop, and adds a back hemisphere to this. It then weaves on the front to create a small door. Some species add a tubular passageway to the back chamber — this can be upto five times the length of the nest.

Why, you might wonder, are these nests so distinctive? Well, the evolution of birds’ nests generally took place via natural selection, the deciding question being whether the young could survive long enough to leave the nest and be successful. But with weaver birds, mate selection is at work — most features of these nests are aesthetic. They are based on the subjective experience of the chooser who decides, ‘Do I like that?’ These nests are built almost entirely by the male.

When a female selects a mate, she selects him — and his nest! This is atypical — robins or penguins, for instance, build a nest together. But the weaver bird female chooses the male’s nest, which has driven its aesthetic evolution. Its long doorways and elaborations are the result of such aesthetic differences, evident in the architectures of human dwellings.

The weaver birds therefore show that a selection for beauty leads to greater diversity than a selection for mere physical functions. Human activity disrupts nest-building in many ways. There are deeply negative processes, such as cutting down trees. But one interesting thing humans have done is to introduce new materials into the world — thread, rope, many fabrics. Birds often adopt these. I grew up in Vermont, America. My mom would knit us bright orange hats. She once suggested we put the extra yarn out in our yard. We did — and a cedar waxwing bird built a nest incorporating this yarn!

The parents successfully raised their young in this bright orange nest. In the Yale Museum, we have a rare nest of a common yellowthroat located inside a boot from the 1890s — it’s a discarded boot, with a hole in the sole. Somebody clearly threw it out but then, this little bird nested inside it. It’s the only recorded instance of this species housing itself in a human object. New materials impact birds — and their innovations impact human beings.

I will never forget that bird’s nest in Vermont, made with bright orange yarn. Its memory stays forever with me.

Birds have been building nests for over 100 million years. Dinosaurs, the ancestors of birds, also built terrestrial nests over hundreds of millions of years. The diversity we see in birds’ nests today is a result of these thousands of bird species, evolving in different environments, creating diverse ways to house and protect a family. We think of architecture as a consequence of conscious design, purpose and aesthetic expression — there is precisely such architecture in avian nests. These are not haphazard constructions. These are shaped by a history of selection and functionality.

Also, the diversity of materials used by birds to build nests is astonishing — and birds arrive at these independently. As adults, they go out into nature alone and gather materials to construct their nests which have very specific structures. These are extraordinary building capacities which show both flexibility and an innate way of interacting with the environment. Interestingly, all nests perform a physical job — to house and protect a bird’s eggs, most vulnerable to weather and predators. The nest is also often the location of the development of the young.

Therefore, knowing the nest’s centrality, birds have developed habitat-based strategies to meet these needs. Diverse species use sticks, twigs, webs or mud, handled in specific ways to create the nests they require. Like human builders, birds choose materials related to the actual structure they want. Birds’ nests also have persistent styles of construction — these are historically contingent, like human communities which use bricks or shingles. Birds have a similar historical investment in their nests. For instance, a group of land birds, which includes kingfishers, hornbills, toucans and woodpeckers, is about 60 million years old. All of these nest in holes, from ground burrows to holes in trees, where they can safely keep their eggs. None of them has created an alternative way.

Nests are therefore conservative structures — birds don’t change the designs much, unless they are sure they are improving on the conditions required for breeding and protecting their young. Now, weaver birds are an extraordinary example of a group that makes spectacular nests. These include an egg chamber suspended from a branch, with a doorway. The complexity is amazing — the fibres are interlaced, like weaves. This creates very strong water-repellent structures. The weaver bird starts with a vertical ring, like a hoop, and adds a back hemisphere to this. It then weaves on the front to create a small door. Some species add a tubular passageway to the back chamber — this can be upto five times the length of the nest.

Why, you might wonder, are these nests so distinctive? Well, the evolution of birds’ nests generally took place via natural selection, the deciding question being whether the young could survive long enough to leave the nest and be successful. But with weaver birds, mate selection is at work — most features of these nests are aesthetic. They are based on the subjective experience of the chooser who decides, ‘Do I like that?’ These nests are built almost entirely by the male.

When a female selects a mate, she selects him — and his nest! This is atypical — robins or penguins, for instance, build a nest together. But the weaver bird female chooses the male’s nest, which has driven its aesthetic evolution. Its long doorways and elaborations are the result of such aesthetic differences, evident in the architectures of human dwellings.

The weaver birds therefore show that a selection for beauty leads to greater diversity than a selection for mere physical functions. Human activity disrupts nest-building in many ways. There are deeply negative processes, such as cutting down trees. But one interesting thing humans have done is to introduce new materials into the world — thread, rope, many fabrics. Birds often adopt these. I grew up in Vermont, America. My mom would knit us bright orange hats. She once suggested we put the extra yarn out in our yard. We did — and a cedar waxwing bird built a nest incorporating this yarn!

The parents successfully raised their young in this bright orange nest. In the Yale Museum, we have a rare nest of a common yellowthroat located inside a boot from the 1890s — it’s a discarded boot, with a hole in the sole. Somebody clearly threw it out but then, this little bird nested inside it. It’s the only recorded instance of this species housing itself in a human object. New materials impact birds — and their innovations impact human beings.

I will never forget that bird’s nest in Vermont, made with bright orange yarn. Its memory stays forever with me.

Download

The Times of India News App for Latest India News

Subscribe

Start Your Daily Mornings with Times of India Newspaper! Order Now

All Comments ()+^ Back to Top

Refrain from posting comments that are obscene, defamatory or inflammatory, and do not indulge in personal attacks, name calling or inciting hatred against any community. Help us delete comments that do not follow these guidelines by marking them offensive. Let's work together to keep the conversation civil.

HIDE